The complexity problem in modern web development

Fifteen years ago, I worked on my first consulting project with Gordon Food Services (GFS) in Grand Rapids, Michigan. We were tasked with building an application called "Customer Item List Manager Plus" (CIL+); essentially a tool that allowed store owners to browse and select food items they needed from their food distributor.

The constraints were significant. The backend was a Java web application using Struts 2, and any Java dependencies had to go through the client's "Software Acceptability Council"; a vetting panel that strictly controlled what could be added to the codebase. As an example of some challenges this caused, when one of our developers wanted to introduce Google Guava for a more functional programming style, it was denied.

This is a common situation in consulting. We rarely have the luxury of choosing whatever technology we want. Instead, we must work within existing constraints and get creative with our solutions.

Our solution? We leaned heavily on JavaScript for the frontend to enhance the user experience, sometimes augmenting server-rendered HTML fragments, but also making use of JSON via Jersey/Spring REST endpoints. The backend team didn't consider JavaScript a "real language" and didn't care what we did with it. This gave us freedom to enhance the user experience without fighting backend constraints. We used libraries like YUI and Knockout to add interactivity while keeping business logic on the server.

Fast forward to today. The web development landscape has changed dramatically. React, Angular, Vue, and other JavaScript frameworks dominate. We've moved from server-rendered pages with "JavaScript sprinkles" to JavaScript-dependent single-page applications (SPAs) with complex state management and a web of dependencies.

But has this shift been entirely positive? Have we gone too far down the path of complexity? (Spoiler alert: it sure feels like it!)

A tale of two applications

Prefer seeing HTMX in action rather than just reading about it? I've created complete example applications that demonstrate everything discussed in this article. Check out the video walkthrough where I compare identical apps built with React and HTMX side-by-side, or dive directly into the code repositories on our GitLab to explore the implementation details yourself.

To explore this question, I built two functionally identical applications using different approaches:

- A single-page application using React and Vite

- A server-rendered application, progressively enhanced with HTMX

Both applications have a user interface that displays invoices and allows users to view and create them. They look and function identically to the user; at least when JavaScript is enabled.

But there's a key difference: the HTMX application works perfectly well with JavaScript disabled, while the React application shows nothing but a blank screen.

Now, I know what you're thinking: "Ok, grampa, when was the last time you actually disabled JavaScript in your browser?" And that's a fair point! The progressive enhancement argument often falls flat because most users do have JavaScript enabled.

However, the real issue goes deeper than just supporting browsers without JavaScript or the purity of progressive enhancement. It's about the architectural complexity that SPAs introduce.

The hidden cost: Duplicated logic

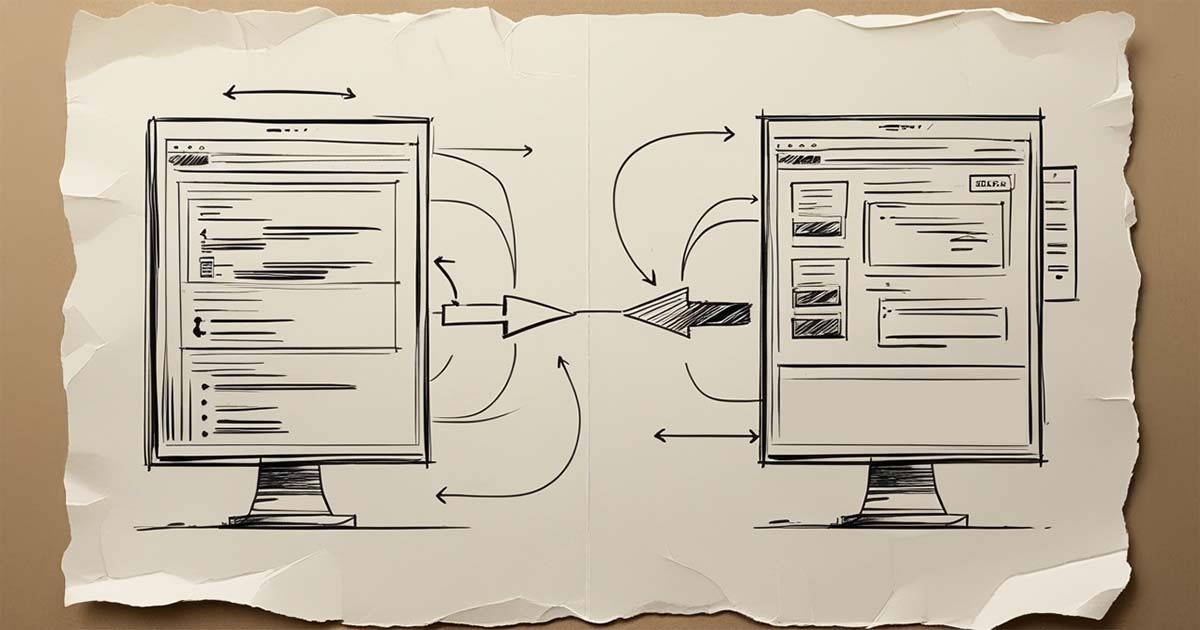

When building a single-page application, you essentially have to implement key functionality twice. Consider routing: your SPA needs client-side routing to navigate between views without page reloads. But your backend also needs routing to serve the correct JSON data to each view. You're duplicating the same logic in two places.

The same applies to data validation, business rules, and even view layouts. With React, you define your UI components on the client, while your server focuses on data. This separation sounds clean in theory, but in practice, it often leads to duplicated effort, potential inconsistencies, and a reimplementation of behaviour browsers give us by default.

In our invoice example, the React version requires:

- Client-side routes for each view

- API endpoints on the server to provide data

- State management to handle loading states, errors, and user interactions

- Separate validation logic on both client and server

The HTMX version, by contrast, centralizes most of this logic on the server, with the client simply requesting and rendering HTML fragments.

Deployment complexity

This architectural split also complicates deployment, especially when your backend uses a different language than JavaScript. Now you're maintaining two separate applications that must be deployed and synchronized. The HTMX approach means you're using server-rendered fragments which means you can deploy a single, cohesive application.

Framework complexity spirals

You might say, "But what about full-stack JavaScript frameworks? Don't they solve this problem?" Frameworks like Next.js, Remix (now React Router), and others do attempt to bridge this gap, but they often add even more complexity in the process.

These frameworks reinvent wheels that traditional server-side applications have had for decades, creating new concepts like:

- Client-side routing with server-side fallbacks

- Complex state management patterns

- Framework-specific quirks (React hooks, context, dependency arrays, etc.)

- Increasingly blurred lines between server and client (server components, islands architecture)

- A bewildering array of rendering strategies (SSR, ISR, CSR, hydration, partial hydration...)

Each of these approaches comes with its own mental model and edge cases to understand. What started as a quest for a better user experience has evolved into a labyrinth of complexity.

The HTMX approach, while it may seem old-fashioned, actually addresses many of these issues by maintaining a clearer separation between client and server responsibilities while still delivering a modern, responsive user experience for most line-of-business web applications.

What is HTMX?

HTMX provides a way to access modern browser features directly from HTML, without writing JavaScript. It's a single script tag you include in your page; no NPM, no bundler, no complex build system.

HTMX extends HTML to answer questions like:

- Why should only anchor and form tags make HTTP requests?

- Why should only clicks and form submissions trigger requests?

- Why are only GET and POST methods easily available?

- Why should every interaction require a full page reload?

With HTMX, you add attributes like hx-post, hx-get, hx-swap, and hx-target to your HTML elements, and HTMX handles the rest. For example:

<button hx-post="/clicked" hx-swap="outerHTML"> Click Me</button>When a user clicks this button, HTMX sends a POST request to "/clicked" and swaps the button with whatever HTML comes back from the server. No JavaScript required (beyond the HTMX library itself).

Comparing implementation approaches

Let's examine how these different approaches influenced the development experience.

The HTMX approach

In the HTMX version, I used Deno on the backend with Nunjucks as the templating language. The entry point is a layout file with template blocks for different parts of the page.

The core pattern for HTMX is:

1. Write your HTML using server-side templates

2. Add HTMX attributes to enable interactivity

3. Handle both JavaScript-enabled and JavaScript-disabled scenarios

For instance, when a user clicks on an invoice in the list, HTMX will:

1. Make a GET request to fetch that invoice's details

2. Update only the invoice detail area (not reload the whole page)

3. Update the URL for proper browser history

The server needs to be aware of whether a request comes from HTMX (a "boosted" request) or a regular browser request. HTMX adds special headers to requests it makes, allowing the server to adjust its response accordingly.

function isHtmxRequest(request) { return request.headers.get("HX-Request") === "true";For an HTMX-boosted request, the server returns just the HTML fragment needed. For a regular request, it returns the full page. This ensures the application works regardless of JavaScript availability.

The single-page application approach

The React version follows the standard SPA pattern:

1. Load a minimal HTML shell

2. Load JavaScript

3. JavaScript renders the entire UI

4. JavaScript handles routing and state management

It's more focused on components, hooks, and state management. While this provides powerful capabilities for complex interfaces, it comes with significant overhead:

- Larger bundle sizes

- Dependency management challenges

- No functionality without JavaScript

The benefits of starting with the server

The HTMX approach offers several key advantages:

- Resilience: It works even when JavaScript fails to load or execute.

- Simpler mental model: You work directly with HTML and HTTP rather than abstract component lifecycles.

- Lighter dependency load: One script tag versus dozens or hundreds of NPM packages.

- Clearer separation: Server handles business logic, client handles UI enhancements.

- Incremental adoption: Can be added to existing server-rendered applications.

Perhaps most importantly, it aligns with the web's original design as a hypermedia system. Links and forms make HTTP requests; servers return documents. HTMX extends this model rather than replacing it.

When to choose each approach

Does this mean everyone should abandon React and embrace HTMX? Not necessarily. Each tool has its place:

Consider HTMX when:

- You're enhancing a legacy server-rendered application

- You value progressive enhancement and accessibility

- Your application is primarily content or form-driven

- You want to minimize client-side complexity

- You need to work with strict backend constraints

An SPA may be better when:

- You're building highly interactive, stateful interfaces

- Your application requires complex client-side logic

- You need offline functionality

- Your team already has strong React expertise

- You're building something truly "app-like" rather than "document-like"

Conclusion

I believe we've overcomplicated web development. For many applications, perhaps 80-90% of what we build, a server-rendered approach progressively enhanced with HTMX provides a simpler, more robust solution than a JavaScript-heavy SPA.

HTMX is decidedly "old school" in its approach, embracing the fundamentals of the web rather than fighting against them. But sometimes the old ways have wisdom to them.

In our rush to build ever more sophisticated client-side applications, we've created a tangle of dependencies and complexity that often doesn't serve our users or our development teams well. React Server Components attempt to bridge this gap, but they blur the lines between client and server in ways that can be confusing rather than clarifying.

The unification efforts of modern JavaScript frameworks often result in more complexity, not less. Each framework introduces its own paradigms, workarounds, and "magic" that developers must learn and debug. Rather than solving the client-server division, these frameworks often create new abstractions that leak implementation details in unexpected ways.

HTMX, by contrast, keeps these boundaries clear while still providing modern interactivity. The server renders HTML; the client enhances it. This clarity makes applications easier to reason about, debug, and maintain over time.

As consultants who spend much of our time "putting spreadsheets on the internet," we should consider whether we can solve problems in simpler ways with fewer dependencies. Most business applications don't need the full complexity of the React or "modern" JavaScript ecosystem. They need reliable ways to display, collect, and process data; something the web was originally designed to do quite well.

HTMX offers one path back to that simplicity without sacrificing modern user experiences. It's not the right tool for every job, but it's a valuable approach that deserves consideration, especially when working within constraints or enhancing existing applications. Sometimes, embracing the web's core technologies rather than fighting against them is the most pragmatic solution.

Dave Mosher is a Principal Consultant at Test Double, and has experience in legacy modernization, agentic coding, and explaining CORS poorly to people who didn't ask.